An excerpt from the book A Driven Mind by Garry Sowerby

It was mid-summer of 1987 and I had been on airplanes between Tierra del Fuego, at the bottom of South America, and Canada for almost 24 hours. The ordeal involved a milk-run flight with five stops up to Buenos Aires and a red-eye to Miami. I then flew to Toronto and connected to an Air Canada flight bound for Nova Scotia.

Looking somewhat rumpled, I was just drifting off when a well-dressed man in the next seat offered to buy me a drink.

“Up in Toronto for a few days?” His name was Bill MacLennan and he was obviously in chat mode.

Over a double gin and tonic I explained I’d been in South America on a final planning trip before attempting to break the existing 56-day record for the fastest drive from the bottom to the top of the Americas. My goal was to complete the 23,500-kilometre route from the southern tip of Tierra del Fuego, Argentina to Prudhoe Bay, on Alaska’s northern coast, in 25 days or less.

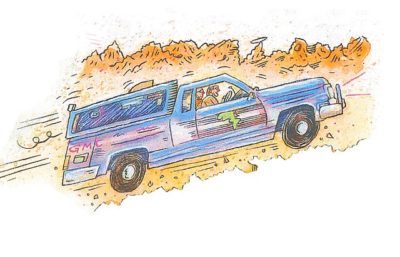

My partner, Montana-based writer Tim Cahill, and I would be driving a then-new 1988 GMC Sierra pick-up truck. The truck had been completely re-engineered for 1988 and General Motors was anxious to give it a real-world workout.

On the flight, I learned Bill MacLennan was President of Farmers Co-Operative Dairy in Nova Scotia which was about to begin marketing milkshakes in long-life Tetrapacks.

“If I give you $5,000, will you take a thousand milkshakes on your adventure?” He looked sincere.

“How about 500, and you ship another 500 to Panama City for us to pick up on our way through?” I countered. A deal was struck.

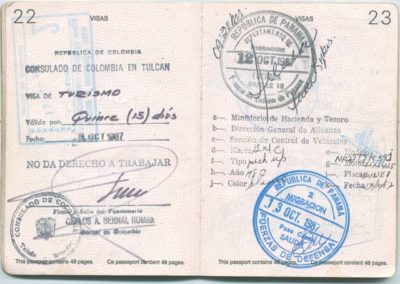

Final preparations seemed endless. A mountain of paperwork had to be processed to obtain visas, letters of introduction and customs documents for the truck. The Sierra was prepped with auxiliary lights, an air horn, winch and a snazzy paint job. A fiberglass cap over the pick-up bed covered a sleeping bunk, food, tools and emergency equipment. It also housed a 350-litre auxiliary fuel tank capable of filling the stock tank three times with the flick of a switch in the cab.

The truck could go 4,000 kilometres without stopping for fuel, plenty of range to dodge questionable fuel stops on the back roads of South America. We would be safe when we were moving.

However, one basic necessity was lacking. We couldn’t figure how to get hot water into the cab of our truck at road speed which was essential to ‘cook’ the freeze-dried food we had on board. It was also needed for a fundamental road trip ingredient. Coffee.

The day before embarking Tim bought a water-heating coil that plugged in to the cigarette lighter. He obviously had stumbled upon a piece of gear that would enable us to dine like royalty while blasting through the jungles of South America.

By the end of Day 1, we realized the heating coil did not live up to expectations. It took 20 minutes to heat a cup of water which was deemed ineffective on the jarring roads we were dealing with.

Freeze-dried curried chicken whipped up with cold water was revolting and drinking cold instant coffee made with soda water produced a scary state of stomach turbulence. It soon became clear that the 500 milkshakes would be our best source of nourishment. At times we mixed the frothy contents with instant coffee for a rudimentary version of café mocha.

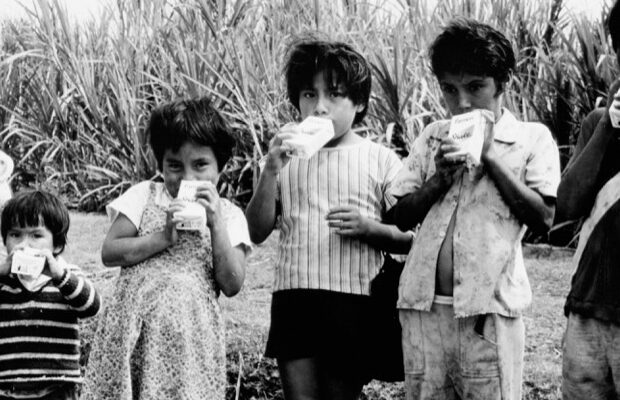

Later, at one of the dozens of roadside controls, we stumbled on another use for the milkshakes. While Tim and I used primitive Spanish to explain what we were up to, heavily armed police focused on the Farmers Milkshake I was drinking. Tim offered shakes to them as well as a group of wide-eyed children who had gathered. The children cheered. The once-menacing officers now jovially slapped us on the back.

Milkshake bribery sessions became ritual. We calculated that even if we drank 10 each a day, we still had 300 milkshakes to get us through the checkpoints between Argentina and Colombia.

In Peru, the pump that transferred fuel from the auxiliary tank went on the blink, so I crawled over the tools, supplies and equipment stored under the fiberglass cap to rectify the problem. In the process I crushed a few cases of shakes causing the milky froth to ooze into the cargo bed. The incident proved fortunate.

At the Colombian border, an official was unimpressed with our letters of introduction. He didn’t care that the Tourism Minister in Honduras saw our record attempt as a good thing for people considering a visit to Tegucigalpa, its capital city. A cute picture of my three-year old daughter strategically placed beside the insurance papers didn’t phase him either. He insisted we empty the contents of the truck to prove we were not carrying contraband or prohibited goods into his country.

When I opened the tailgate, Tim and I, along with a half dozen curious officers, reeled back in disgust. The putrid smell of souring milkshakes from the crushed cases was repulsive.

“Pedazo de carne mala!” I accused Tim of being a bad piece of meat.

He returned the compliment and everyone broke up. We handed out strawberry shakes in the midst of the bizarre tailgate party and were soon on our way. Milkshakes had pulled us through again.

We reached the port city of Cartagena on Colombia’s Caribbean coast in time to rendezvous with a container ship that took us through the Panama Canal. Delighted with our progress, we considered the worst was behind us.

As long as another 500 Farmers Milkshakes were waiting in Panama City.

Follow Garry on Instagram: @garrysowerby