“Le Petit Palais, c’est fermée au jour d-hui!”, (The Petit Palais is closed today!) the stonefaced soldier barks, imposing a change to our plans. My wife and I think he’s lying but know he’s holding a rifle, so don’t argue.

Today, publication day, is June 6, 2025, exactly 81 years after D-Day, but this story starts a month earlier, on VE-Day’s 80th Anniversary. And you’d think central Paris would feel celebratory.

Instead, the vibe’s unsettling, like they’re expecting trouble. Tall unsmiling servicemen in riot gear flank both sides of the Champs Elysées, kettling us would-be celebrators behind temporary fences and makeshift cement barriers.

One of Paris’s most famous art museums, the Petit Palais is 100m away but closed to those trapped on the wrong side of this instant No Man’s Land. The victory parade and celebrations at the Arc de Triomphe — ostensibly a flyover and some speeches — don’t kick off for three hours.

Should we wait under tightening surveillance or walk away?

We’re lucky. The Musée D’Orsay is open till 9pm Thursdays and features not only some of the world’s greatest artworks but a fairy tale restaurant in a Belle-Epoque ballroom whose painted ceiling is pinch-me ornate. So later, while President Macron delivers his sombre speech within view of the Petit Palais, we’re enjoying a chilled Viognier with moules awash in a buttery wine sauce, having just enjoyed miles of masterpieces.

81 years ago, the Allies understood, too, that changing plans is part of having them, though theirs were infinitely more challenging and consequential.

Also, they were not as lucky. D-Day launched a day late due to inclement weather and, if further postponed, would’ve had to wait for a couple more weeks for the right tides. But they didn’t have the option to walk away.

May 9, 2025, Caen, Normandy — “I propose to you an offer.”

The car renter’s trying to upsell us from an Opel Corsa to a big SUV. Some auto writers would call the Opel une boîte à merde but its engine easily achieves the local speed limits; its basic rental price includes several proximity alerts to help prevent scratches, plus a manual transmission for that genuine European experience; and we’re traveling light with just carryon luggage. Most important though, Norman roads can suddenly shrink to suck-in-your-gut narrowness. Why pay for a bigger car?

We keep the Opel and drive a half hour to Normandy’s postcard-perfect town of Bayeux with its famously narrow roads and stunning skyline. It emerges like the City of Oz but is 3D.

Ever been to Normandy? This place is more renowned for its cider and butter than artists and perfumers. Yet it’s hard to overstate how present history is here in this otherwise sleepy corner of northeastern France.

Especially the World Wars.

On a country hike, the stump you trip over may turn out to be shrapnel. Many of the roads are named after British generals. A fishing and boating shop across the street from the D-Day beach in Arromanches is bizarrely called Winnipeg Equipement.

It’s no exaggeration to say the D-Day battle fought here is one of the most important in Western history. But D-Day’s not the only historic turning point Normans live daily.

At 12 Euros, the Bayeux Tapestry may be the best museum value anywhere in France.

70 metres long and 900 years old, the flawless Bayeux Tapestry is an embroidered cartoon depicting the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, led by Guillaume le Batard, aka Bastard Bill, later rebranded as William the Conqueror.

All behind protective glass experience, the presentation is ingenious. Everyone viewing the tapestry gets headphones with narration in the language of your choice. You’re narrated and literally walked through the story, panel by panel, down a dark hall, the tapestry brightly lit from behind. You’re barred from taking pictures which, uninterrupted, draws you deeper into the gripping ancient comic book tale.

Did you know that to this day, the invasion of 1066 deeply affects all of us here in Canada and America? Decapitating England’s leadership overnight, it also remolded our language into an Anglo-Saxon-cum-Latin smorgasbord over generations.

Today, the idea of a local boy kicking England’s ass is still as sweet to Normans as 900 years ago. The Bastard’s still one of their own.

Next morning in the nearby village of Ryes, an elderly paysan couple notice us taking photos of Saint-Martin, the thousand-year-old church where the 8-year-old would-be Conqueror William hid and then escaped from would-be assassins. He took a back-country route now called the Pente de Batard (Bastard Path) which the pair points us to. History’s hiding in plain sight here if slightly grown over in places.

But what these two passing villagers are most excited to tell us is “le miracle” that this church was spared from the devastation of allied bombing exactly 81 years ago.

Consider. On D-Day alone, the Allies dropped 10,395 tons of bombs in Normandy.

There’s a ridiculous but persistent myth that the allies weren’t prepared for the storming of Normandy. Maybe it’s that class dude’s narrative technique: the bigger the other guy is, the tougher you seem by beating him.

Fact 1: By 1944, the German army was a shadow of the comprehensive machine that had seized Europe in 1940. But Fact 2: Defending in any battle is always easier than attacking.

And remember, the Allies were attacking from Britain, a 24-hour boat ride away. Hence, the incredible planning and detailed preparation to present an absolutely overwhelming force.

Just compare the Allies’ payload of 10,395 tons of explosives across 50km of beach on D-Day to the Blitz, 3 ½ years earlier. Over 57-straight nights, the Luftwaffe dropped just 700 tons on London’s 1,940 square km. That’s not even 7% as much as the Allies of D-Day onto just 100-ish square km.

With such explosive might, Normandy was devastated; the sparing of Saint-Martin Church and beautiful Bayeux were, indeed, miraculous.

The Allies had to bring everything with them. They even brought and built harbours.

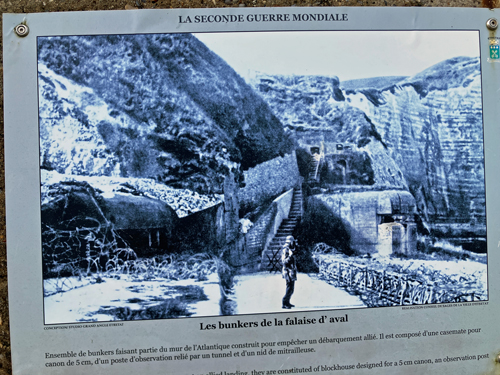

Yes … actual makeshift harbours, nicknamed Mulberries, which they dragged across the English Channel. What audacity. Mulberries enabled the beaching of the heaviest imaginable newly invented machinery, from tanks and cannon-guns to trucks, carrying everything from hospital supplies to food, to ammunition, and even transportable bridges. (Normandy’s original bridges were pretty much gone.)

To this day, the remains of Mulberry Harbour B, hauled here from England, remain in Arromanches Bay. The allies quickly created a seawall behind it with destroyed ships. What gumption! And immensity. Hunks of wall and empty hulks still sit here. Seeing them is as overwhelming as that opening scene of Star Wars except it’s more impressive IRL.

Arromanches was called Gold Beach on D-Day. The British stormed it and Sword Beach. The Americans renamed and took Utah and Omaha Beaches. Between Sword and Gold Beaches, Canada attacked and won Juno Beach.

An apology from a Canadian to his brave forebears: Compared to Gold Beach, which is nestled at the foot of a scenic escarpment, Juno’s kinda flat and ugly. (Imagine any generic B-grade 1980s vacation getaway in trashiest Florida with an upturned German bunker and a lineup of Maple Leaf flags.) We were grateful to have seen the prettier spots first.

But maybe ugly’s good in this case.

The Canadian Encyclopedia reports over 5,000 of our soldiers died at Juno.

Plus 13,700 more injured Canadians were listed as casualties during the entire Normandy invasion. Imagine. Canada’s population in 1944 was 12 million. So that devastating hit to the nation today would mean nearly 16,000 Canadian boys dead, 16,000 Canadian families devastated.

Some more perspective: Over the relatively recent 20-year Afghanistan war, a total of 158 Canadian soldiers were killed — each one an absolute tragedy, yes — but with an impact most Canadians just don’t seem to notice. That the people of Normandy live their history shouldn’t surprise you; what should shock us all is how many Canadians don’t. However, it’s never too late to learn.

Just 400km northeast of Juno sits another legendary Canadian battlefield from another devasting war we ought never forget.

Vimy the town is appropriately grim. Its nearby Canadian WWI monument is haunting.

The tiny villages you drive through to reach the Vimy Memorial seem infected by the region’s heavy history. France suffered 150,000 casualties re-taking this (now) quiet escarpment; Canada suffered over 10,000, 3,598 of whom died. It beggars imagination.

No wonder the monument is overwhelmingly large and sombre — grimly beautiful. Most of the terrain is fenced off with signs screaming DANGER. Though grown over with vegetation, the fields remain pitted from bombs, like some rolling green moonscape. These grounds “still contain live ordnance” explains the tour guide. She’s a bilingual University of Ottawa student supplied by the Canadian government.

Ordnance is military speak for big guns, bombs and ammo. It’s disturbing to think that by hopping a fence 100 years later, we could die in an explosion right now.

The free tour includes descent into a modified WWI tunnel. Keeping the original underground route, the Canadian groundskeepers have expanded it for head- and elbowroom, reinforced it for public safety, and de-ratted it for health and sanity. Even with these careful improvements, the tunnel remains claustrophobic and oppressive.

After our tour, we need a new word. The men who died here were barely out of their childhood. The gratitude this haunted place inspires in us feels meagre and inadequate. History is complicated and never comforting, even when you ‘win’.

Epilogue: The day of this article’s publication marks exactly 81 years since D-Day.

It would be reassuring to think that since we Canadians have left this immense monument in Vimy for posterity … that because the French have left gargantuan remnants of harbours rotting on their beaches … that since these fresh-faced uni-students who are older than most of the soldiers they commemorate are giving these tours … that maybe we can all learn our history’s most vital lessons. And that such horrific carnage won’t be allowed to happen again.

Truly, it would be.