An excerpt from the book Driven Mind by Garry Sowerby

October 6, 1997 – Kerman, Iran

“What kind of weapons are you carrying?”

It was the question I did not want to hear. And the matter-of-fact way that Ahmad Homayouni asked it made me feel even worse. His relatives gathered around the table at his cousin’s home in Kerman, Iran, seemed to be staring right through me.

“Well, we don’t have any weapons,” I replied. I didn’t like where this was headed.

Fifteen seconds. It seemed like an eternity. But for the next fifteen seconds, there was silence in this immense house with a garden in the living room. The half dozen Iranians stared at me as if I was crazy to be heading out unarmed on the desolate 600-kilometre road through Pakistan’s Sandy Desert paralleling the Afghanistan border.

The ensuing conversation confirmed my suspicions about security in West Pakistan. Ahmad and his family explained that the area we were about to drive through was rife with smugglers moving three-cent-a-gallon Iranian gasoline into Pakistan. It was a region where tons of the world’s opium and hashish start the journey to western markets and where gun runners arming Afghani rebels surface from time to time.

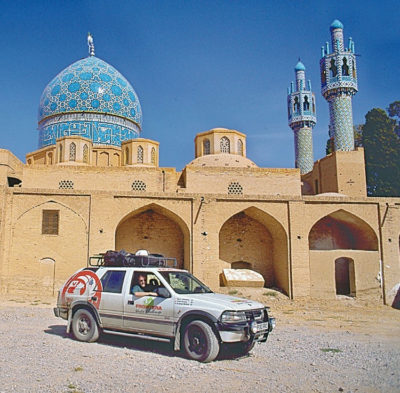

To make matters worse, my new friends assured me the transportation of choice for many of these operatives was four-wheel drive sport utility vehicles. I eyed our grimy four-wheel drive Vauxhall Frontera turbo diesel out front in the driveway. The spare tires and satellite communications antenna on the roof made it looked like a sitting duck.

In the fading desert light, I could just make out the logo on its front door, Frontera World Challenge. A muezzin chant from the mosque down the street filled the air. The heat was stifling. I was exhausted.

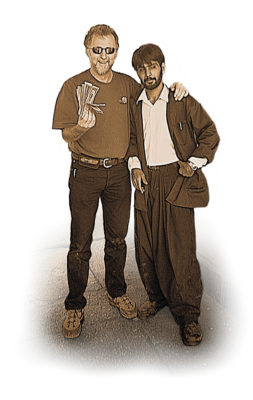

My partners, Welshman Colin Bryant and Scottish-born Graham McGaw, were down the street at the Kerman Grand Hotel. They were trying to overcome a technical glitch in our procedure for uploading digital images back to our logistics office in Canada and the press centre in London, England.

Colin, a retired police officer who spent much of his career driving British heads of state around Wales, was about the best driver I had ever been with in a car. Witty and charming, focused and stubborn, he had already wrestled our overloaded Frontera through many dicey traffic situations.

Graham knew every nut and bolt in our vehicle. He worked as an engineer at the plant where the Frontera was manufactured in Luton, England. His natural curiosity, coupled with plenty of experience with everything from motorcycles to eighteen wheelers, made him ideal for the team.

Since leaving England, we had driven pretty well non-stop. Western Europe was straightforward. Aside from a two-hour traffic jam in Vienna and torrential downpours in Serbia, the 38-hour drive to Sofia, Bulgaria was a good warm-up. Then it was pea-soup fog through the mountains of central Turkey and temperatures of up to 42° Celsius in the desert areas southeast of Tehran.

The rules for the around-the-world driving record we were attempting stipulated that Colin, Graham and I had to drive at least 29,000 kilometres. Backtracking was not allowed, and we had to finish with at least two of us in the car. The route had to pass through two antipodal points – places on the earth’s sphere that are diametrically opposed to one another. Our antipodals were Gisborne, New Zealand and Sagunto, a town just outside of Valencia, Spain.

The clock ran during the continental transits only. Turn it on in London. Turn it off in Chennai, India. On in Perth, Australia. Off in Sydney and so on. So with five stages, the attempt became five record runs with breathers in between where we transform ourselves into logisticians, documenteurs and administrators.

And finally the big ugly. No speeding. Get caught speeding and it’s over in the eyes of Guinness Superlatives, who were sanctioning the attempt. There were a thousand things that could have ended the Challenge, but the idea of disqualification for a speeding ticket didn’t excite any of us. And, since the only way to guarantee one didn’t get a ticket was not to speed, we didn’t. It wasn’t that bad. It kept the stress levels down and we still managed to cover an amazing amount of territory every day.

All the way through the Sandy Desert, I thought about my three young daughters Lucy, Natalie and Layla back home in Nova Scotia. But in my mind’s eye, I couldn’t erase the visual of Graham’s two children, Vikki, 7, and Andrew, 4, hugging their daddy goodbye at the start line. Their skinny outstretched arms reaching for one more embrace before we headed off. I envisioned that scene many times… when an ominous speck on the horizon grew into an approaching vehicle, when we detoured around blasted-out bridges.

But we made it through the Desert without incident. It took three days to get through Pakistan to New Delhi, India. On the second day, the road was so rough it took 17 hours to cover just 600 kilometres. Then it was floods in Multan, bribes to get us out of Pakistan and an 11-hour night drive along India’s Grand Trunk Road that would have made anyone’s hair stand on end. We arrived in New Delhi at three in the morning, maneuvering through a smoggy, ragged fog.

The 2,300-kilometre drive from New Delhi to Chennai (formerly Madras), on the Bay of Bengal in southeast India, was one tough drive. Colin woke up feeling sick in New Delhi and got progressively worse. South of Agra, home of the wondrous Taj Mahal, navigating got complicated. Most of the road signs were in the local script so we couldn’t decipher the alphabet, let alone the words. At one point, a crowd surrounded the car, some banging on the windows with their fists.

The road eventually deteriorated into one lane of pot-holed asphalt. Towns and villages were jammed with creeping trucks carrying huge papier mâché statues of the ten-armed goddess, Durga. Since Durga had the main roads blocked, we had to find alternate routing through back streets, back yards even. As we worked our way south, we saw people dumping her likenesses into lakes and rivers. It was a night I will never forget.

We drove all the next day and into the night along roads choked with chaotic traffic. A car once in a while but mostly trucks, big grotesque ones. Some had one light, some had none. Few had all their lights. But one thing was for certain, any truck with lights had the high beams staring right into our bloodshot eyes.

It had been 36 hours since we left New Delhi and Colin’s condition had degenerated to a point where he was virtually helpless. It was very quiet in the backseat where he was laid out except for a guttural moan whenever Graham or I hit a pothole.

We finally reached Chennai 11 days, 21 hours and 25 minutes after leaving London… five minutes ahead of our self-imposed schedule. We were tired, filthy and Colin was a mess, but we were ecstatic to have reached the end of the first leg in our bid to drive around the world.

For the next two days, Graham checked over the Frontera, Colin recovered at the hotel and I dealt with the Indian bureaucracy. It was rubber-stamp madness as a shipping agent paraded me and a mountain of blurry documents around the port of Chennai. The place looked more like a landfill operation than a major international shipping centre. When word got around about where we had been, the directors of both the Customs and Security departments got involved.

With our papers in order, I drove the Frontera into a well-used six-metre-long container. A giant forklift loaded the container onto a flatbed truck for transport across the port to the ship. In three weeks, our truck would be in Perth, on Australia’s west coast.

Black clouds had filled the sky while craggy forks of lightning danced along the horizon. The humidity was outrageous.

“You were lucky to get to Chennai when you did, Mister Garry,” the Customs official warned.

“Why’s that?” I choked. Billowing dust was making it hard to breath.

“Monsoons — they’re late this year.” He pulled a wax customs seal out of his pocket. “If they had been on time, you would never have gotten through central India.”

Then, as he clamped the seal on the container door, the sky opened up and the monsoons were upon us.