Wine And Spirits

To anyone who appreciates the finer points of taking corners at speed on a racetrack, the word ‘Corkscrew’ means only one thing; turns 7, 8 and 8a at WeatherTech Raceway Laguna Seca. It’s iconic. Get it right and you will be smiling for a least the next 1:25.44 seconds as your work your way back for another go around should you happen to be driving a Czinger 21C Hypercar, the current record holder.

Of course, there is an equally compelling use of the word corkscrew that evokes a sense of surprise and delight as you anticipate the simple joy found in a fine glass of wine or spirits. While it may be a different pleasure than deftly making it through the famous set of turns located just east of Monterey, California, the pleasure is no less intoxicating. In fact, it is certain to last longer than a perfect lap of the racetrack. Scott Patrick Cowan takes us inside the world of wine and spirits with insider knowledge only an expert can share.

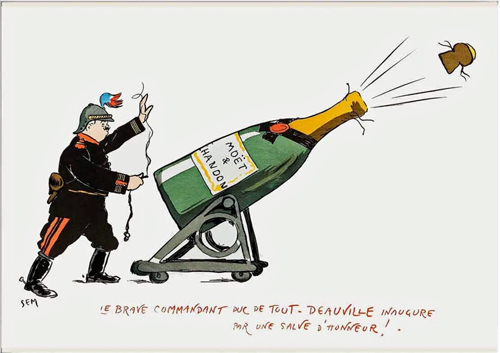

Champagne: War and Yeast

We plunged lower and lower into the ancient chalk quarry. A steely chill confronted us from a prong of subterranean tunnels. Sunlight shuddered through iron grids at street level, glinting toward a mass of bottles like a searchlight over wading water. Silky scum edged toward the neck of every green bottle.

“So,” a voice speculated, “how many of you have tasted Champagne before?”

I raised my hand, hawk-eyed. My girlfriend prayed that I would keep my keener mouth shut.

Did you know that a Champagne cork can travel at 88 kilometres per hour and knock somebody out cold? Did you know that there was a Champagne nazi called the Weinführer and he once jailed the guy at Taittinger for serving the troops fizzy dishwater, he said. Did you know they did wine tastings in the trenches in Champagne during World War I? And…

Hands all raised like it was the River Styx. I never had my chance.

Then, Ployez-Jacqumart. A jewel within the town of Ludes. Family-owned since 1957. Skirting past several world wars, a revolt in 1912 for fair grape grower prices, and a flood in 1911 that had Champagne bottles literally floating down the streets. People hopping in gondolas and making after wayward bottles.

Small Champagne houses can accommodate small appointments. Hosting you even in their living rooms. They can top up the glass until it is hissing near your face. That’s how close you get to the process.

The owner-winemaker, Laurance Ployez, at the end of our tour, asked us, “Did you get to see the house secret?”

I wondered if she meant the medieval cellars of precariously stacked Champagne bottles, all upside down, sur pointe. For a couple of hundred years, 50% of a given cellar would explode spontaneously. The era was called Le Grand Fracas (“The Great Shattering”). Them: “la chaîne du tonnerre” (“The Chain of Thunder”). The poor person with the mop and broom.

Quixotically smiling. Arms outstretched on a paisley 19th century couch. Her lips pursed. The house secret, she told us, was what they put in the wine. The liqueur d’expédition. The lip-smacking coda. Flavour sculpted from chalk. And for a place overwrought with rules (you will see inspectors measuring grapevines) I’ve thought about her response for years. She exploded into laughter like two soldiers in a fox hole getting shelled, clinking their glasses together. “Grape juice,” she said. Grape juice was the house secret.

Stunned, I thought, like Welches? Nowadays, I know she was being playful.

Everyone does this. It’s the olio that made the bottle a brut or an extra brut. Naturally sweetened grape juice.

The in-vogue grower winery Bérèche adds fresh wine to elderly wine in a giant vat, like a bunch of Spaniards around a sherry solera. This fractional blending will go on infinitely, as long as the universe expands and allows Champagne Bérèche et Fils to exist. It’s known as “Reflet d’Antan” (“Reflections of the Past.”).

For the growers to compete with the big houses — who produce 20,000,000 cases each sometimes and with winemakers that cannot share the same flights — they must be propelled to cult-like platitudes. On the back of the bottles made by Henri Giraud, you’ll find a sticker asserting:

PESTICIDE RESIDUES CHECKED BY MOLECULAR ANALYSIS

Champagne is wet, buggy, open, and disease-prone. Conditions waver between splintering hail and dangerous heat waves. It is essentially a set of rolling hills, with a whisper of momentum to push a fog in every direction for miles and miles. Vintners such as Claude Giraud put their lives in figure-eight knots to achieve organics. “The vine must be free,” he announces, and “we must break the chains of industrialization.”

(Did you know that the USSR sent spies to Champagne in order to make Sovetskoye Shampanskoye? Me either.)

The future of Champagne, as sommeliers see it, is a descent into tradition.

In 2010, 168 bottles of Champagne were scooped up from a Baltic shipwreck. Dating as early as 1811, they showed notes of crystallized fruit, caramel, leather, and tobacco. Not a single one of them tasted of fizzy dishwater. Some of them even sparkled a little. Each bottle sold for an average of $100,000 USD.

Guess where some of the more experimental Champagne cellars are today.

Ruinart is the oldest Champagne house. It is also the deepest quarry or “crayères” in the Champagne capital, tunnels going on for miles, and a UNESCO world heritage site.

The personalized Champagne sommelier tour-guide explained, in great depth, that the literal gold plated elevator we were riding in had just been installed. I looked down at myself — in cargo shorts and tennis shoes. Then I looked around at the other people on the tour. All worldly multi-something-aires in cowboy hats, perfectly placed pearls, and mohair suits sartorially measured in millimeters. This was murder mystery attire.

It took us 38 metres deep, where our tour-guide, dressed in a three-piece chalk-stripe suit, practically glided across the floor like Gene Wilder. On the wall, graffiti from the early 20th century of Mickey Mouse, scrawled there by a member of the resistance or a refugee.

Once again, we made our way to a drawing room with ornate couches. However, once the blended wine collapsed onto our tongues in waves of pastry and tart berries, we were all captured. My tongue was perfectly sedated.

My partner looked at me, expecting a lecture about how the coupe is a pretty bad glass for Champagne: it’s not even shaped like Marie-Antoinette’s breast, like they say. I was breathless. I haven’t had this wine since, I should mention, but I hope someday that it will wash ashore onto some beach I am walking. Maybe in the Baltics. Maybe somewhere where the history of celebration and catastrophe collide. Sublime silence in the drawing board room. Then:

“Did you know that the French resistance slipped laxatives into the Nazi’s massive Champagne stash?” somebody said aloud.

“Why, yes,” the Champagne sommelier responded. “It’s true.”